Male and Female Initiated Intimate Partner Violence (IPV): Comparable Beginnings, Unequal Outcomes, Shared Risks

Mentor Research (2025)

Initiation: How Often Do Men and Women Start Violence?

Research across multiple decades has consistently shown that men and women report initiating acts of intimate partner violence (IPV) at comparable rates when surveys use behaviorally specific questions such as “Have you ever slapped your partner?” or “Has your partner ever pushed you?”

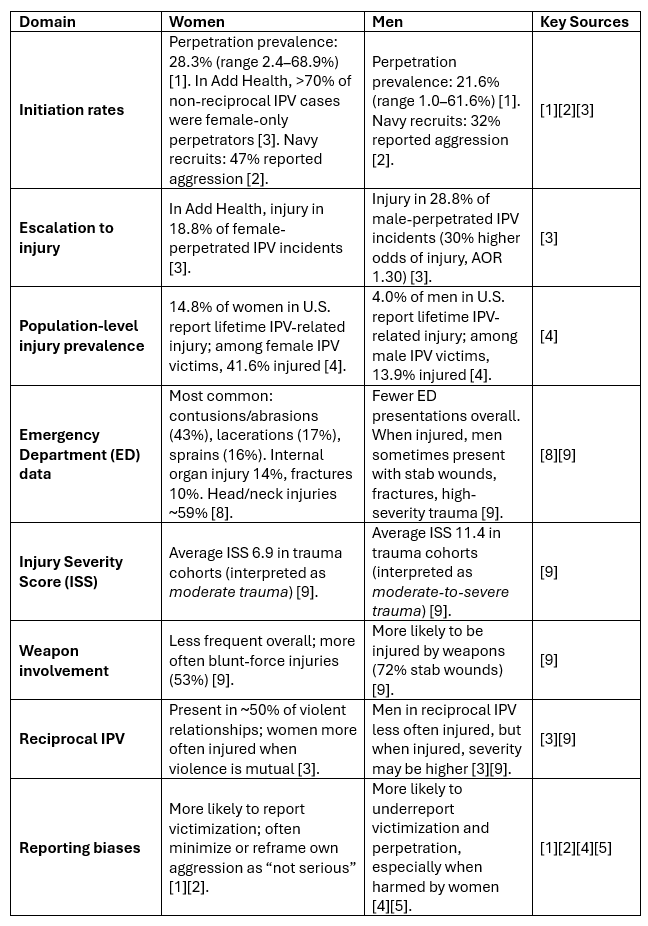

One of the largest systematic reviews, the Partner Abuse State of Knowledge (PASK) project, examined 111 studies across English-speaking industrialized countries. It found pooled perpetration prevalence of 28.3% for women and 21.6% for men [1]. Importantly, the study emphasized wide variability: for women, the range was 2.4% to 68.9%, and for men, 1.0% to 61.6%, depending on study design, populations, and the timeframe examined. This means in some studies women reported much higher initiation, while in others, men did. On balance, the review concluded that initiation rates are “more similar than different.”

Other individual studies echo this apparent symmetry. For example, a survey of U.S. Navy recruits (average age ~20 years) reported 47% of women and 32% of men admitted to some form of physical aggression against a partner in the past year [2]. Similarly, a longitudinal U.S. study of young adults, the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), found that IPV occurred in 24% of relationships, with roughly half classified as reciprocal violence. In relationships where violence was non-reciprocal, women were the sole perpetrators in more than 70% of cases [3].

It is critical to note that these figures reflect initiation of acts, not patterns of coercive control. Women more often report starting with behaviors such as slapping, pushing, or throwing an object, whereas men more often report behaviors like punching, choking, or restraining [5]. The vast majority of men attempt to retrain a woman first. This distinction matters because although women “start” an altercation, and they escalate when restrained. The acts themselves begin with lower immediate lethality.

Still, the data make one point clear: in terms of who strikes first or who initiates at least one act of IPV, the genders appear comparable, and in some contexts (alcohol, stimulant drug use, etc.), women report higher rates of initiation.

Summary Table: Male- and Female-Initiated IPV – Initiation, Escalation, Injuries, and Reporting

Escalation: Why Consequences Diverge After Initiation

Although men and women may initiate IPV at similar rates, what follows after initiation differs in important ways. The available evidence does not suggest that men inevitably or even commonly escalate a minor provocation into a severe assault. What it does show is that, when men do perpetrate IPV, the acts they report are more likely to involve behaviors with higher injury potential, and the outcomes are more likely to include physical harm.

The Add Health study illustrates this difference. When IPV was perpetrated by men, 28.8% of incidents resulted in injury, compared to 18.8% when perpetrated by women. This means male-perpetrated IPV carried a 30% higher odds of producing injury (Adjusted Odds Ratio = 1.30, 95% CI 1.10–1.50), and the finding was statistically significant [3].

Population data confirm this trend. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) reported that 14.8% of U.S. women and 4.0% of U.S. men had been injured as a result of IPV in their lifetimes, roughly a 3- to 4-fold difference [4]. When looking only at those who had experienced IPV, 41.6% of women victims versus 13.9% of men victims reported being injured [4].

The types of acts used during escalation explain much of this disparity. Meta-analyses show that women more often report using slapping, shoving, or throwing objects, while men more often report punching, restraining, or striking with greater force [5]. These behaviors differ not only in intent but in the probability of producing medically significant injuries. For example, bruises and abrasions are consistent with minor injury categories (AIS 1, ISS 1–3), whereas broken bones or internal injuries fall into moderate-to-serious categories (AIS 2–4, ISS 9–15+) [6][7].

The point is not that men inevitably escalate disproportionately, but rather that the distribution of injury-producing acts differs by gender. Women are certainly capable of inflicting serious harm, studies of male victims show stab wounds and high-severity trauma are common, but across large datasets, men’s IPV produces more injuries on average.

Types of Injuries: Comparing Patterns and Severity

Injuries to Women

The NISVS reports that 14.8% of women in the U.S. have sustained injuries due to IPV, compared with 4.0% of men [4]. Among women who experienced IPV, nearly 42% reported being injured at some point [4]. Common injuries include bruises, contusions, lacerations, sprains, and fractures, with women also reporting high levels of fear, PTSD symptoms, and coercive control [4][5].

Emergency department data reinforce this picture. Across 1.65 million IPV-related ED visits over nine years in the U.S., the most frequent injuries among women were contusions/abrasions (43%), lacerations (17%), and sprains/strains (16%) [8]. Yet serious injuries were not rare: internal organ injuries occurred in 14% of visits, and fractures in 10%. Injuries to the head and neck were the most common, representing about 59% of all IPV-related trauma [8].

Injuries to Men

Although men report lower rates of IPV-related injury overall, studies show that male victims often sustain highly severe trauma when violence is female-initiated or occurs in reciprocal contexts. A trauma center study found that men admitted for IPV-related injuries had an average Injury Severity Score (ISS) of 11.4, compared to 6.9 for female victims, a meaningful difference, as an ISS above 9 indicates moderate trauma and scores above 15 indicate major trauma [9].

In that same cohort, 72% of male victims were admitted for stab wounds, while women were most often admitted for blunt-force assaults (53%) [9]. This suggests that while men may report fewer injuries overall, those injuries can be medically complex and life-threatening.

Severity Scores in Context

The Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) and Injury Severity Score (ISS) provide context for what these injuries mean clinically.

Minor injuries such as small bruises or abrasions correspond to AIS 1 and ISS 1–3, which usually do not require hospitalization.

Moderate injuries such as large lacerations, some fractures, or mild head trauma fall in AIS 2–3 and ISS 4–9, often requiring ED care.

Serious injuries such as major fractures, stab wounds, strangulation effects, or internal organ injury correspond to AIS 3–5 and ISS 9–25, with higher risk of disability or death [6][7].

For women, these more serious injuries are more common numerically, given the larger number of female victims overall. For men, although fewer in frequency, the injuries that do occur often fall disproportionately into the higher severity ranges.

Table: Biomechanical Asymmetry in IPV Acts

Development, Socialization, and Physiological Responses

Male Responses to Aggression and Threat

From an early age, boys are often socialized into hegemonic masculinity, where toughness, restraint of emotion, and physical dominance are prized [21]. Aggressive impulses may be channeled into structured and socialized outlets such as sports, especially contact and combat sports. Studies of male athletes show that participation in such sports is linked to greater approval of and engagement in physical violence compared to non-athletes [8][12].

This socialization intersects with male physiology. In both animals and humans, males often respond to threat with freezing or motionless restraint—a “stone-cold” demeanor that signals control and minimizes perceived vulnerability [5][11]. Evolutionary theories, such as the male warrior hypothesis, suggest that suppression of fear and reliance on calculated aggression were adaptive in intergroup conflict and survival [20]. The aggressor will attack in other demonstrates behavior associated with fear or physical weakness.

The implication for IPV is clear: a slap or shove from a female partner may not destabilize a man physically, but if he responds, his greater average strength and training in controlled aggression may result in harm far beyond the initial act. Trauma cohort studies show that when men are injured by partners, they often present with high ISS scores (~11.4), commonly from stab wounds [9].

Female Responses to Aggression and Threat

Girls and women are socialized differently. From early development, they are encouraged to manage conflict through words, observation, and avoidance rather than direct confrontation [21]. Aggression in female peer groups is more likely to take the form of relational aggression than overt physical violence [21].

Physiological research suggests that women may more commonly rely on the “tend-and-befriend” response to stress, using social support, words, or withdrawal as primary strategies [19]. When women do initiate aggression, it is often through slaps, pushes, or thrown objects [5]. These acts are violent, even if sometimes minimized as “not serious.” Many women act under the assumption that men will exercise restraint. When that assumption fails, the result is often a dramatic escalation in harm.

At the same time, women may resort to weapons as a means of offsetting physical disadvantage. This helps explain why male victims, while fewer in number, sometimes sustain disproportionately severe injuries such as stab wounds, organ trauma, or fractures [9].

Reciprocal Violence: When Both Partners Use Force

One of the strongest predictors of serious injury in IPV is whether the violence is reciprocal. In relationships where only one partner is violent, the likelihood of injury is lower, though still serious. But when both partners use violence, the risk of harm rises dramatically.

The Add Health study found that when both partners were violent, the odds of injury were 4.4 times higher compared to relationships with non-reciprocal violence [3].

This pattern reflects the reality that escalation is not a solution. When women initiate violence and their partner responds in kind, they are often met with greater retaliatory force. While women’s initiation may begin with a shove, slap, or thrown object, male partners who respond are more likely to escalate to actions with higher injury potential [5].

Studies of emergency department and trauma center populations confirm this asymmetry. Women more often sustain injuries overall, but men, when injured, sometimes present with life-threatening trauma such as stab wounds [9]. Reciprocal IPV thus harms both genders: women sustain more injuries overall, men sometimes sustain more severe ones.

Gendered Reporting: Who Tells What, and Why It Matters

Women often minimize their own aggression, framing slaps and pushes as “not serious” or defensive [1][2]. Men frequently underreport victimization, especially when harmed by female partners [4]. This creates a double distortion: female aggression is undercounted, and male victimization is underrecognized.

Survey design amplifies this. Behaviorally specific questions narrow the gender gap (revealing symmetry in acts like slapping or pushing), while broad terms like “abuse” magnify female victimization reports [1][5]. The truth is complex: women may initiate frequently but minimize reporting; men may be seriously injured but fail to disclose.

Conclusion: Comparable Beginnings, Divergent Outcomes

The evidence demands a balanced conclusion. Men and women initiate IPV at broadly similar rates. Yet escalation diverges: women sustain injuries more often, men sometimes sustain more severe trauma. Reciprocal violence multiplies the risk for both. And reporting biases mask the reality of female aggression and male victimization.

Aggression is aggression. Violence is violence. Both genders use it, both sustain harm, and both deserve recognition. To reduce IPV, we must move beyond counting who started it, and focus on escalation, injury, and the socio-biological asymmetries that shape outcomes.

References

Desmarais, S. L., & Reeves, K. A. (2012). Prevalence of physical violence in intimate relationships: Part 2. Rates of male and female perpetration. Partner Abuse, 3(2), 170–198. https://doi.org/10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.170

Swan, S. C., Gambone, L. J., Caldwell, J. E., Sullivan, T. P., & Snow, D. L. (2008). A review of research on women’s use of violence with male intimate partners. Violence and Victims, 23(5), 563–577. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.23.5.563

Whitaker, D. J., Haileyesus, T., Swahn, M., & Saltzman, L. S. (2007). Differences in frequency of violence and reported injury between relationships with reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence. American Journal of Public Health, 97(5), 941–947. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.081554

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_report2010-a.pdf

Archer, J. (2002). Sex differences in physically aggressive acts between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 7(4), 313–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-1789(01)00061-1

Palmer, C. (2007). Major trauma and the Injury Severity Score – where should we set the bar? Scandinavian Journal of Surgery, 96(1), 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/145749690709600109

Medscape. (2024). Trauma Scoring Systems: Overview, Applications, Calculation (ISS/AIS). eMedicine. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/434516-overview

Loder, R. T., Momper, L., & Meyer, L. E. (2020). Demographics and fracture patterns of patients presenting to U.S. emergency departments for intimate partner violence. JAAOS: Global Research & Reviews, 4(2), e20.00006. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-20-00006

Vasquez, J., & Falcone, R. (2015). Injury patterns in male versus female victims of intimate partner violence. Journal of Emergency Medicine, 48(3), 320–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.10.018

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.107.3.411

Gruene, T. M., Flick, K., Stefano, A., Shea, S. D., & Shansky, R. M. (2015). Sexually divergent expression of active and passive conditioned fear responses in rats. eLife, 4, e11352. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.11352

Vertonghen, J., & Theeboom, M. (2010). The social-psychological outcomes of martial arts practice among youth: A review. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 9, 528–537. https://www.jssm.org/jssm-article/528

Connell, R. W. (1987). Masculinities and violence: The role of culture and socialization. In Gender and Power (pp. 236–276). Stanford University Press. https://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=1825

Wrangham, R., & Peterson, D. (1996). Demonic Males: Apes and the Origins of Human Violence. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. https://www.hmhbooks.com/shop/books/Demonic-Males/

Black, M. C. (2011). Intimate partner violence and adverse health outcomes: An overview. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 5(5), 428–439. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827611410265

Niolon, P. H., Kearns, M., Dills, J., Rambo, K., Irving, S., Armstead, T., & Gilbert, L. (2017). Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Across the Lifespan: A Technical Package of Programs, Policies, and Practices. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/45543

Taylor, J. C., Bates, E. A., Creer, A. J., & Colosi, A. (2022). Barriers to men’s help seeking for intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(19-20), NP18417–NP18444. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211035870

Foran, H. M., & O’Leary, K. D. (2008). Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(7), 1222–1234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411-429. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.107.3.411

Van Vugt, M., De Cremer, D., & Janssen, D. P. (2007). Gender differences in cooperation and competition: The male-warrior hypothesis. Psychological Science, 18(1), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01842.x

Björkqvist, K. (1994). Sex differences in physical, verbal, and indirect aggression: A review of recent research. Sex Roles, 30(3-4), 177-188. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01420988

CDC Core References

DC IPV Overview and Definitions

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). CDC Division of Violence Prevention.

https://www.cdc.gov/intimate-partner-violence/about/index.html

Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements

Breiding, M. J., Basile, K. C., Smith, S. G., Black, M. C., & Mahendra, R. R. (2015). Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 2.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC.

https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/31292

National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS)

Smith, S. G., Zhang, X., Basile, K. C., Merrick, M. T., Wang, J., Kresnow, M., Chen, J., & Leemis, R. W. (2022). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2016/2017 Report on Intimate Partner Violence. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC.

https://www.cdc.gov/nisvs/documentation/NISVSReportonIPV_2022.pdf

Risk and Protective Factors for IPV

CDC. Risk and Protective Factors for Intimate Partner Violence.

https://www.cdc.gov/intimate-partner-violence/risk-factors/index.html

Prevention and Programmatic Work

CDC. Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Across the Lifespan: A Technical Package of Programs, Policies, and Practices (2nd Edition). Atlanta, GA: CDC, Division of Violence Prevention, 2023.

https://www.cdc.gov/intimate-partner-violence/prevention/index.htmlCDC. DELTA AHEAD (Domestic Violence Prevention Enhancement and Leadership Through Alliances: Achieving Health Equity through Addressing Disparities).

https://www.cdc.gov/intimate-partner-violence/programs/index.html

Economic Impact of IPV

Peterson, C., Kearns, M. C., McIntosh, W. L., Estefan, L. F., Nicolaidis, C., McCollister, K. E., & Florence, C. (2018). Lifetime Economic Burden of Intimate Partner Violence Among U.S. Adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 55(4), 433–444.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.049

Complementary CDC and Federal Resources

CDC’s Violence Prevention Resource for Action

CDC. Violence Prevention Resource for Action (formerly known as the Technical Packages). 2023 update.

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/programs/resource-for-action.html

CDC’s VetoViolence Learning Hub

CDC. VetoViolence — Online Training and Tools on Preventing IPV.

https://vetoviolence.cdc.gov/

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC) Overview of IPV

CDC NCIPC. Preventing Intimate Partner Violence.

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/index.html

Supporting Research and Context

Health Consequences of IPV

Black, M. C. (2011). Intimate Partner Violence and Adverse Health Outcomes: An Overview. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 5(5), 428–439.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827611410265

Early Onset and Developmental Trajectories

Niolon, P. H., Kearns, M., Dills, J., Rambo, K., Irving, S., Armstead, T., & Gilbert, L. (2017). Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Across the Lifespan: A Technical Package of Programs, Policies, and Practices. Atlanta, GA: CDC, Division of Violence Prevention.

https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/45543

Peterson, C., Kearns, M. C., McIntosh, W. L., Estefan, L. F., Nicolaidis, C., McCollister, K. E., & Florence, C. (2018). Lifetime Economic Burden of Intimate Partner Violence Among U.S. Adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 55(4), 433–444.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.04.049

Complementary CDC and Federal Resources

CDC’s Violence Prevention Resource for Action

CDC. Violence Prevention Resource for Action (formerly known as the Technical Packages). 2023 update.

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/programs/resource-for-action.html

CDC’s VetoViolence Learning Hub

CDC. VetoViolence — Online Training and Tools on Preventing IPV.

https://vetoviolence.cdc.gov/

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC) Overview of IPV

CDC NCIPC. Preventing Intimate Partner Violence.

https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/index.html

Supporting Research and Context

Health Consequences of IPV

Black, M. C. (2011). Intimate Partner Violence and Adverse Health Outcomes: An Overview. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 5(5), 428–439.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827611410265

Early Onset and Developmental Trajectories

Niolon, P. H., Kearns, M., Dills, J., Rambo, K., Irving, S., Armstead, T., & Gilbert, L. (2017). Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Across the Lifespan: A Technical Package of Programs, Policies, and Practices. Atlanta, GA: CDC, Division of Violence Prevention.

https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/45543