Sex-Based Brain Differences and Relational Dynamics in Couples Therapy

Mentor Research (2025)

Abstract

This training article provides a comprehensive overview of sex-based structural brain differences and their influence on attachment, emotion regulation, stress responses, and communication in intimate relationships. By translating findings from neuroscience, particularly the structural connectome, into clinically relevant insights, the article guides relationship therapists in integrating psycho-neuro-endocrine knowledge into couples’ therapy. Key differences in male and female brain connectivity and neurobiology are presented alongside implications for relational behavior. Comparative tables highlight male versus female brain features relevant to therapy. Clinical reflection sections offer practical psychoeducational techniques to help couples appreciate these differences with empathy rather than judgment. The goal is to enrich therapeutic practice with accessible science, fostering understanding and collaboration between partners (Tunç et al., 2016; Ingalhalikar et al., 2014).

Introduction: Bridging Neuroscience and Couple Therapy

Modern couples therapy resides at the crossroads of neuroscience, psychology, and social dynamics. Over the past decades, research has confirmed that while men’s and women’s brains are far more similar than different, certain sex-related neurobiological differences do exist and can subtly shape relational behavior (Joel et al., 2015; Ingalhalikar et al., 2014). These differences are not about one sex being “better” or “worse”; rather, they reflect evolutionary and developmental variations in brain structure and connectivity. For therapists, understanding these nuances can provide a powerful framework for explaining common relationship patterns, such as pursuer–withdrawer dynamics or miscommunication under stress, in a biologically informed, non-blaming way (Taylor et al., 2000; Gottman & Levenson, 1992).

Couples often misinterpret each other’s behaviors through a moral or emotional lens, e.g., “She’s overreacting,” or “He just doesn’t care.” A neuroscience-informed perspective offers more compassionate explanations: partners’ brains may genuinely process stress or emotional cues differently (Taylor et al., 2000; McRae et al., 2008). By educating couples about such brain-based differences, therapists can help depersonalize conflicts (“it’s not that my partner won’t understand; their brain might literally be tuning in differently”) and foster mutual empathy (McRae et al., 2008; Newhoff et al., 2015).

This article reviews key sex-related brain differences in the structural connectome, the wiring diagram of neural connections, and relates them to four domains crucial in relationships: attachment and bonding, emotional processing and regulation, stress response, and communication. Each section translates scientific findings into practical clinical insights, with suggestions for psychoeducation and interventions that clinicians can use to improve couples’ understanding and connection.

Clinical Insight – A Balanced Perspective

When discussing sex differences, it is crucial to emphasize to clients that averages do not determine individuals. There is wide variability, and many differences are small in effect size (Joel et al., 2015). The goal is never to stereotype or limit partners, but to offer possible explanations for why certain patterns occur, and to validate both partners’ experiences as equally real. The wise therapist, frames brain differences as complementary strengths rather than deterministic traits.

The Structural Connectome: How Male and Female Brains Are Wired

Neuroscientists mapping the structural connectome (the brain’s network of white-matter pathways) have uncovered robust sex-related patterns in connectivity. In a landmark diffusion tensor imaging study of 949 young people, Ingalhalikar et al. (2014) found that, on average, male brains show significantly more within-hemisphere neural connectivity, whereas female brains show more between-hemisphere connectivity. In other words, male brains tended to have stronger front-to-back connections within each hemisphere (facilitating coordinated perception–action loops), while female brains had stronger left-to-right connections between hemispheres (facilitating integration of analytic reasoning with intuitive and social processing) (Ingalhalikar et al., 2014). Tunç and colleagues (2016) extended this work and linked these structural patterns to sex differences in behavior, showing that males’ enhanced intra-hemispheric connectivity is related to motor and spatial performance, while females’ inter-hemispheric and inter-modular connectivity relates to social cognition, memory, and attention (Tunç et al., 2016). PubMed+1

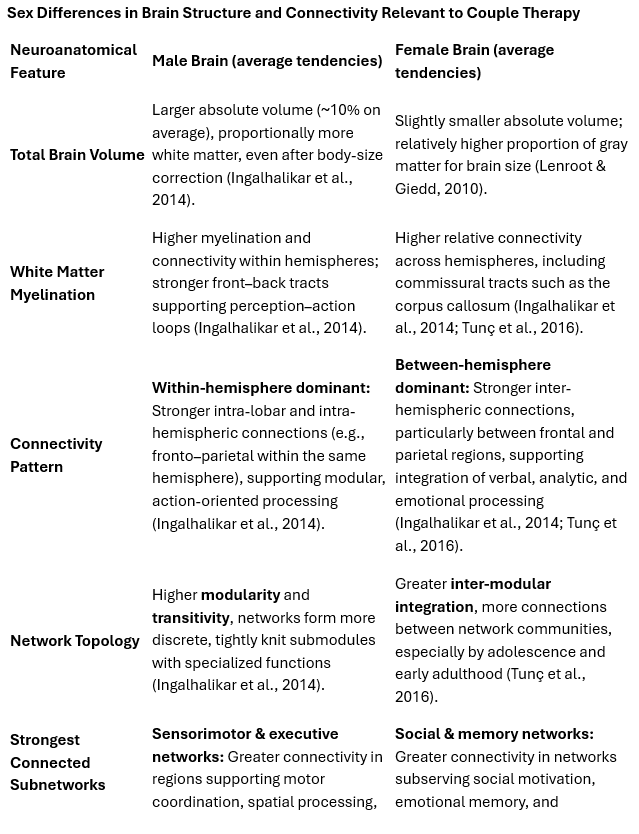

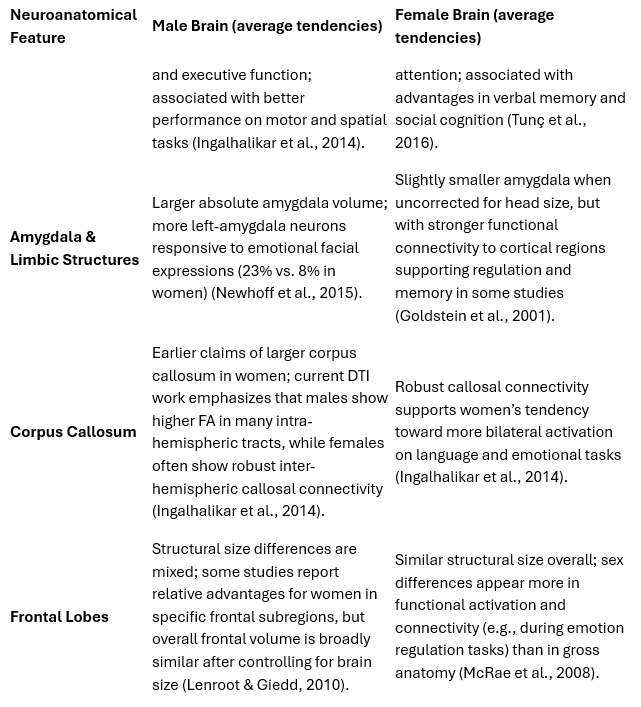

These fundamental differences in network architecture are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

Summary of key brain structural and connectome differences between males and females. These population-level tendencies may influence how each sex processes information and responds to the social environment (Ingalhalikar et al., 2014; Tunç et al., 2016; Newhoff et al., 2015).

Researchers interpret these patterns as reflecting complementary evolutionary specializations. The male brain’s bias for within-hemisphere, front–back connectivity creates an “action-oriented” network optimized for perceiving and responding to the physical environment (Ingalhalikar et al., 2014). The female brain’s stronger cross-hemisphere links facilitate integration of analytical and intuitive processing, effectively weaving together logic, language, and emotion (Ingalhalikar et al., 2014; Tunç et al., 2016).

It is important to note that these are statistical trends with substantial overlap; individual brains do not neatly sort into “male” or “female” wiring types (Joel et al., 2015). Nonetheless, the trends can help explain certain behavioral tendencies that often (though not always) differ between men and women in relationships. For example, females’ more integrated social and memory networks may contribute to better recall of relational details and heightened attunement to social cues (Ingalhalikar et al., 2014; Tunç et al., 2016), while males’ more localized visuospatial/motor connectivity aligns with strengths in spatial navigation or mechanical problem-solving (Ingalhalikar et al., 2014).

Clinical Insight – Introducing Brain Differences to Clients

The following is an example of how to frame an introduction of brain differences:

“Research using brain scans finds that, broadly speaking, women’s brains tend to be wired a bit more like a web, lots of cross-connections, whereas men’s brains have somewhat more local wiring in each side. During an emotional discussion, one partner’s brain may light up with memories, feelings, and words all connected, while the other partner’s brain channels energy into one focused strategy or even shuts down. Neither is wrong, these are different wiring patterns. Let’s figure out how to use those differences as strengths rather than weapons.”

This framing normalizes differences and moves the conversation away from blame.

Attachment and Bonding: Neural Bases of Connection and Distance

Attachment style, our habitual way of seeking closeness or protecting ourselves from hurt, is influenced by both early experience and biology. Large surveys and meta-analyses indicate that, in heterosexual samples, male partners are somewhat more likely to exhibit avoidant attachment behaviors (distancing, needing space), while female partners are slightly more likely to show anxious attachment behaviors (pursuing closeness and reassurance) (Kirkpatrick & Davis, 1994). The sex differences are modest overall, but they are clinically visible. Socialization clearly plays a role; however, neurobiology adds important detail.

Limbic Circuits and Attachment

The amygdala, a central structure for processing fear and social threat, behaves somewhat differently on average in men and women. As noted earlier, single-neuron recordings from the human amygdala showed that a significantly larger proportion of left-amygdala neurons in men responded to emotional facial expressions compared to women’s responses (Newhoff et al., 2015). Thier heightened reactivity may predispose some men to be unconsciously vigilant to emotional demands, potentially triggering a “flight” or “freeze” (avoidant) response when intimacy feels overwhelming.

In contrast, women’s amygdala responses are often more tightly coupled with hippocampal and prefrontal regions involved in memory and regulation, which may support richer, more interconnected emotional recollection (Goldstein et al., 2001). An anxiously attached woman may vividly recall past hurts and relational episodes, fueling her urge to seek reassurance when an attachment alarm is activated.

Oxytocin and Social Reward

Oxytocin, the so-called “bonding hormone”, affects attachment behavior in sex-dependent ways. Animal and human research suggests that females’ brains are more sensitive to oxytocin’s social rewards, making affiliative interactions particularly soothing and rewarding (Taylor et al., 2000; Borland et al., 2019). In simple terms, connection often feels intensely good to many women at a biological level, driving them toward nurturing and proximity under stress (Taylor et al., 2000).

Males produce and respond to oxytocin as well, particularly in close contact or paternal caregiving; however, circulating testosterone can dampen oxytocin effects, and there is evidence that males may not experience the same magnitude of stress-reduction from closeness in all contexts (Taylor et al., 2000; Borland et al., 2019). This could subtly contribute to men’s being more comfortable with distance or autonomy in relationships.

Stress Systems and Attachment Dynamics

When an anxiously attached person fears losing their partner, the HPA axis is strongly activated, increasing cortisol and adrenaline. Here, sex-linked stress patterns often emerge. Taylor’s “tend-and-befriend” model proposes that females, under stress, are more likely to seek social support and caregiving as a primary coping strategy, mediated by oxytocin and female sex hormones (Taylor et al., 2000). In contrast, males are somewhat more likely to default to fight-or-flight responses, either becoming confrontational or withdrawing (Taylor et al., 2000).

Over time, these tendencies can crystallize into the familiar anxious–avoidant couple dance. The more one partner pursues (attempting to tend-and-befriend), the more the other withdraws (fight-or-flight), and vice versa. Each is biologically trying to regulate stress, and their strategies clash.

From a clinical standpoint, knowing these mechanisms helps validate each partner’s experience. The partner who says, “I feel panic when she pulls away, like I’m in free fall,” is not “clingy”; their attachment system may truly be sounding an alarm of danger. The partner who says, “When he comes at me with criticisms, my mind goes blank and I just need to get away,” is not necessarily choosing to be insensitive; his nervous system may be flooding to the point where emotional processing shuts down.

Gottman and Levenson (1992) found that men’s physiological arousal (heart rate, etc.) during conflict tends to spike higher and take longer to return to baseline compared to women’s, a form of flooding that led many men to be the “stonewallers” in heterosexual couples. Teaching couples about these expectable patterned responses can replace blame with a sense of shared challenge: “Our nervous systems are doing something predictable; how do we help them function better together?”

Clinical Insight – “Me or My Biology?”

In attachment work, therapists can introduce the idea that “your body may be reacting in old, hard-wired ways that don’t perfectly fit your current relationship.” Encourage partners to externalize the reaction (e.g., “my attachment alarm is going off,” or “my turtle-shell response kicked in”) rather than attacking one another’s character.

A practical agreement might be:

The more anxious/pursuing partner practices signaling early distress (“My alarm is going off”) and choose to use self-soothing tools before escalating pursuit.

The more avoidant/withdrawing partner might practice saying, “I’m overwhelmed and need 20 minutes, but I will come back,” rather than disappearing.

Framing these moves as caring for each other’s brains, which are likely to have different stress thresholds, can be a powerful intervention.

Psychoeducational Techniques for Attachment Differences

Attachment Cycle Diagram

Draw the classic pursuer–withdrawer loop and annotate each node with biological states (e.g., “amygdala alarm,” “cortisol spike,” “avoidant shutdown,” “oxytocin craving for closeness”). This helps couples see they are not just “difficult people,” but two nervous systems struggling with a feedback loop.Evolutionary Narrative

Explain ways anxious protest and avoidant suppression had survival value in ancestral contexts (Kirkpatrick & Davis, 1994; Taylor et al., 2000). This reframe often reduces shame and deepens compassion.Oxytocin-Focused Interventions

Suggest experiments like a 20-second nonsexual hug, gentle handholding or mutually agreed touch rituals during or after conflict de-escalation. These behaviors can increase oxytocin, lower cortisol, and create a felt sense of safety for both partners (Taylor et al., 2000).

Emotional Processing and Regulation: Different Routes to the Same Goal

Partners often experience, express, and regulate emotion in distinct and sex-linked ways. Clinically, you may notice patterns such as one partner (often female in heterosexual couples) who processes emotion by talking and elaborating, while the other (often male) becomes terse, silent, or highly focused on problem-solving. These styles are shaped both by socialization and brain circuitry.

Limbic Activation Patterns

When processing emotional stimuli, studies show sex differences in brain activation. In many tasks involving emotional or social content, women exhibit stronger and more widespread activation in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), insula, and parts of the prefrontal cortex, regions involved in empathy and emotion labeling (Altavilla et al., 2021). Women also frequently show right-lateralized engagement of the amygdala and prefrontal regions when processing negative social scenes (Altavilla et al., 2021).

In contrast, men sometimes display a more focused limbic response, with stronger left-amygdala activation to certain emotional stimuli and less widespread cortical involvement (Newhoff et al., 2015). Single-neuron work by Newhoff and colleagues (2015) demonstrated that a greater proportion of neurons in men’s left amygdala responded to emotional faces than in women’s, suggesting a dense but more narrowly tuned sensitivity.

Cognitive Reappraisal vs. Suppression

McRae et al. (2008) examined how men and women down-regulate negative emotion using cognitive reappraisal. Behaviorally, both sexes reported similar reductions in negative affect. Neurally there were striking differences:

Men showed less increase in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activity (the “effortful rethinking” region) and greater decreases in amygdala activity during reappraisal.

Women showed more sustained frontal engagement and somewhat less amygdala dampening.

The authors interpreted this as evidence that men’s brains may implement reappraisal or suppression more automatically or efficiently, while women engage more conscious cognitive resources to regulate emotion (McRae et al., 2008). In a relational context, this can look like:

The male partner: “I just stop thinking about it or move on,” reflecting efficient neural dampening, sometimes at the cost of awareness.

The female partner: “I need to talk it through to feel better,” reflecting active cognitive processing and integration of the emotional experience.

Emotional Expression and Recognition

Women tend to outperform men on tasks of emotion recognition, reading facial expressions and tone of voice more quickly and accurately (Hall & Matsumoto, 2004). Correspondingly, women’s brains show higher activation in areas supporting social cognition and face processing (e.g., fusiform gyrus, superior temporal sulcus) during such tasks (Proverbio et al., 2008). Women also typically display a wider repertoire of nonverbal emotional expressions.

Men, while capable of high emotional intelligence, may require more explicit cues to access these circuits. Newhoff et al. (2015) found that, while more neurons in men’s amygdala reacted to emotional faces, this did not translate into greater overt emotionality; instead, men demonstrated quicker but less elaborated responses. Clinically, this can appear as “flat” or “limited” affect even when internal emotions are significant.

Clinical Dynamics

Common dynamics include:

The expressive partner (often female) saying: “He’s so unemotional, I never know what he’s feeling.”

The more contained partner (often male) saying: “She goes on and on about feelings, why can’t we just let it go?”

Both perceptions are understandable. The more contained partner may internally feel overwhelmed but be relying on suppression or compartmentalization, which minimizes outward signs. The more emotionally expressive partner’s brain may keep generating associations (memories, meanings), fueling the need to verbalize to integrate their experience.

Clinical Insight – Emotion Coaching Between Partners

Given these processing differences, each partner can grow by stretching toward the other’s style.

The less expressive partner can practice naming at least one feeling and offering a simple, honest statement (e.g., “I feel hurt and overwhelmed; I need a break in the conversation but I care about this”). This turns an invisible internal state into something relational.

The more expressive partner can practice tolerating a bit of silence and choose to reduce verbal volume or speed so the other’s slower processing style is respected.

This is not about making one style “right,” but about building a shared emotional language.

Techniques for Emotional Regulation Differences

“Name It to Tame It” (Siegel, 2012)

Teaching clients that labeling emotion reduces amygdala activation and engages prefrontal regulation can be especially useful. Encourage the more suppressive partner to verbalize one feeling, even if it feels awkward, and encourage the more expressive partner to distill their experience initially into a few core emotion words rather than a long narrative.Written Processing Before Live Discussion

If a partner freezes or becomes defensive in real time, suggest writing out feelings beforehand. This engages language networks without an immediate interpersonal stress. The other partner might read (or hear what was read) and respond later, lowering the emotional intensity in face-to-face dialogue.Mindfulness and Grounded Breaks

Both partners benefit from learning to recognize early signs of emotional flooding (Gottman & Levenson, 1992). Teaching them to take a 20 to30-minute break when flooded, during which they engage in self-soothing activities and avoid ruminating, helps them restore prefrontal control. This is framed as brain maintenance, not avoidance.Empathy-Building “Switching Hats” Exercise

Have each partner describe an argument from the other’s internal perspective, including likely bodily sensations and brain states. This can be structured as a short narrative or roleplay and can be particularly powerful when informed by brain science the therapist has already introduced.

Stress Response Differences: Fight, Flight, or Tend-and-Befriend

Relationship conflict is a stressful event for partners (and family members) with attached/attuned nervous systems. Autonomic and endocrine responses to stress may differ systematically by sex, shaping how partners (and families) handle conflict and high-pressure life events.

Physiological Arousal and Recovery

Gottman and Levenson (1992) showed that men’s heart rate, blood pressure, and skin conductance increase more rapidly and stay elevated longer during marital conflict than women’s, indicating faster and more sustained sympathetic activation. Once men’s heart rates exceed about 100 beats per minute, their ability to process language and respond constructively plummets, a state Gottman termed flooding. Women also flood, but average thresholds and recovery times differ modestly.

For couples, this means that the male partner may be physiologically incapable of productive dialogue at a lower level of apparent conflict than the female partner. Continuing to “talk it out” in that state may escalate a quarrel into a fight.

Hormonal Cascades: Testosterone, Cortisol, Estrogen, and Progesterone

Under acute stress, testosterone in men may temporarily increase, modulating dominance and assertiveness (Archer, 2006). In arguments, this can show up as sharp, defensive posturing or competitiveness. Over time, however, chronic cortisol suppresses testosterone, contributing to fatigue, reduced libido, and withdrawal (Sapolsky, 2004). Clinically, some men cycle from explosive engagement to long periods of apparent indifference, reflecting underlying endocrine shifts rather than simple “not caring.”

Women’s endocrine responses are also entangled with menstrual and reproductive hormones. Estrogen boosts serotonergic and dopaminergic transmission, often supporting sociability and optimism during the follicular phase (Schoep et al., 2019). Rising progesterone in the luteal phase can enhance threat sensitivity and stress reactivity, especially when combined with premenstrual drops in estrogen (Farage et al., 2009).

As noted in reading the psychoneuroendocrine paper, the neurochemical turmoil of postpartum or menopause can dramatically amplify stress reactivity and affect regulation. These contexts are important to explore explicitly with clients in midlife or perinatal transitions.

Tend-and-Befriend vs. Fight-or-Flight

Taylor et al. (2000) proposed that, behaviorally, females’ responses to stress are often marked by “tend-and-befriend”, caring for offspring and seeking social affiliation, rather than pure fight-or-flight. Oxytocin and endogenous opioids underlie this pattern. In many couples, this translates to the female partner reaching for connection under relational stress (wanting to talk, hug, or “fix us”), while the male partner, driven by sympathetic activation, may either escalate or withdraw.

Clinical Reflection – The 20-Minute Rule

Emphasize that the strategy of taking a 20-minute break when flooded is not avoidance but alignment with biology. Adrenaline and noradrenaline require time to metabolize. During the flooding window, higher-order reasoning is compromised (Gottman & Levenson, 1992; Lisitsa, 2013). Framing time-outs as neuroprotective and as pre-agreed upon can increase compliance and reduce feelings of rejection or abandonment.

Techniques for Managing Different Stress Responses

Structured Time-Out Agreements

Collaboratively design a time-out protocol with a neutral signal (e.g., “I’m getting flooded; I need 20 minutes”), clear rules (no new arguments via text, no ruminating), and a set time to reconvene. This is especially crucial for partners who are prone to stonewalling.Co-Regulation Exercises

Teach couples simple practices like synchronized breathing, back-to-back breathing, or a brief “heart hug” where they focus on each other’s breathing and warmth. These exercises leverage oxytocin and vagal activation to reduce arousal and support mutual soothing (Taylor et al., 2000).Aftercare Rituals

Encourage brief rituals after conflict, such as a walk, shared tea, or a “repair statement” (“I love you; I don’t like how that went; I’d like to do better”). These rituals signal to both nervous systems that attachment is intact, and reduce the likelihood of lingering hypervigilance.Balancing Tend-and-Befriend and Self-Regulation

Support the typically more affiliative partner (often female) in developing self-soothing skills so that all regulation does not depend on immediate closeness. Conversely, support the more avoidant partner in experimenting with tending behaviors (small gestures of comfort) which may need to be learned, and can be deeply regulating for both.

Communication and Cognitive Style: Talking “Through” the Brain Differences

Communication in intimate relationships requires integration of emotional, cognitive, and social brain networks. Sex-related differences in brain organization and development influence communication styles, especially under stress.

Language and Bilateral Processing

Women often show advantages in verbal fluency and certain language tasks (Halpern et al., 2007). Combined neuroimaging and lesion studies suggest that women may recruit more bilateral cortical networks for language and emotion, whereas men tend to show more lateralized patterns (Ingalhalikar et al., 2014). In conversation, this may appear as:

A more talkative, descriptive style (often female), with focus on nuance and context.

A more concise, problem-focused style (often male), oriented toward “bottom-line” solutions.

These patterns likely reflect both cultural and gender norms and the underlying connectome differences reviewed earlier.

Memory for Relational Events

Women tend to outperform men on episodic memory tasks, especially for emotional and relational events (Herlitz & Rehnman, 2008). Their brains encode such events with rich sensory and affective detail. Men often retain the gist but not specific details or emotional micro-steps. Clinically, this shows up as:

One partner recalling past conflicts with striking specificity (“You said this exact phrase three months ago at dinner with my sister”).

The other having a fuzzier recollection or feeling ambushed by the level of detail.

Therapists are wise to validate that both memory styles are legitimate. One is detail-oriented, the other gist-focused; both can inform repair and growth.

Problem-Solving vs. Emotional Processing

As highlighted in discussion of the psychoneuroendocrine model, many male clients orient toward fixing the problem quickly, in part to reduce their own discomfort with dysregulated affect. Their action-oriented fronto–parietal networks engage rapidly (Ingalhalikar et al., 2014). Female clients, in contrast, may derive genuine soothing from being heard and understood before any problem-solving occurs, drawing on their highly integrated social-cognitive systems.

If these expectations are unspoken, the conversation collapses: one feels dismissed by quick solutions, the other feels helpless in the face of “endless talking” that doesn’t culminate in an actionable plan.

Clinical Insight – Two “Native Languages”

A helpful metaphor is that partners are speaking different native communication “dialects”:

One speaks “Emotionalese” (rich in adjectives, context, and process).

The other speaks “Factish” (concise, solution-focused).

The therapeutic goal is not to erase these dialects but to help each partner to become bilingual.

Techniques to Harmonize Communication Styles

Speaker–Listener Protocol (Neuroscience Framing)

Introduce a structured turn-taking practice: one partner speaks for 1–2 minutes; the other reflects what was said. Explain that this prevents cognitive overload and supports the brain’s limited working-memory capacity. Ask the more verbose partner to pause regularly and the concise partner to elaborate including at least one emotion.“What I Said / What I Meant” Table

Use a simple table with two columns for each partner:What I said: e.g., “You never help me.”

What I meant / felt: e.g., “I feel overwhelmed and scared that I’m alone in this.”

Completing such a table outside the heat of conflict appeals to the logical, analytic brain while it makes visible various underlying attachment needs.Shared Emotional Vocabulary

Introduce an emotion wheel or list and invite both partners to identify words that fit their experiences during recent conflicts. The less verbally fluent partner can point or circle words rather than generating them spontaneously. Over time, this increases emotional granularity and supports more precise communication.Tech-Assisted Communication

For couples where one partner processes slowly, encourage asynchronous communication (e.g., email or written notes) before a face-to-face conversation on sensitive topics. This allows for thoughtful formulation of emotions and needs and can prevent in-session or at-home flooding.

Conclusion: Integrating Brain-Based Insights into Practice

The human brain, whether male or female, is an attachment organ, a social organ, and a resilient organ. Sex-based structural differences may predispose certain default tendencies, but they do not dictate destiny. The interpersonal value of understanding these differences expands the capacity for empathy and intervention options, not in reinforcing stereotypes.

As they teach couples about their psycho-neuro-endocrine patterns, therapists help them move from a stance of “What’s wrong with you?” to “What’s happening between our nervous systems, and how can we respond differently?” Couples gain language for describing their experiences, flooding, shutdown, attachment alarm, oxytocin craving, problem-solving mode, without blaming orself-attack.

Neuroscience also offers hope through neuroplasticity. New patterns of co-regulation, communication, and conflict resolution, practiced repeatedly, literally reshape circuits over time. Couples can learn to temper the sharp edges of sex-linked differences and cultivate complementarity:

One partner may bring focus, decisiveness, and calm into chaos.

The other may bring emotional awareness, social sensitivity, and contextual nuance.

When consciously integrated, these differences can become a dyadic asset. The structural connectome provides a map; intentional relational practice determines the route.

As a neutral and opinionated perspective, I suggest that relationship therapists:

Normalize sex-linked differences in brain and stress responses as one part of the puzzle, never the whole story.

Use brain-based explanations sparingly but strategically to reduce shame and blame.

Tie every bit of psychoeducation to a concrete skill (e.g., time-outs, empathic listening, co-regulation exercises).

Stay alert to intersection factors, gender, culture, sexuality, trauma history, that modulate how the biological tendencies manifest.

My qualified recommendation is that these neurobiological insights be woven gently into your existing model/s of couple work (EFT, IBCT, Gottman, PACT, Developmental Model), just as you are doing in your MRI training, rather than presenting such ideas as a freestanding “neuroscience module.” When integrated well with various other interactions, they may deepen both therapist and client compassion and sharpen precision of relational interventions.

References

Altavilla, D., Ciacchella, C., Pellicano, G. R., Cecchini, M., Tambelli, R., Kalsi, N., & Lai, C. (2021). Neural correlates of sex-related differences in attachment dimensions. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 21(1), 191–211. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-020-00859-5

Archer, J. (2006). Testosterone and human aggression: An evaluation of the challenge hypothesis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 30(3), 319–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.12.007

Borland, J. M., Aiani, L. M., Norvelle, A., Grantham, K. N., O’Laughlin, K., Terranova, J. I., Ferrell, A. D., Baek, M., & Albers, H. E. (2019). Sex-dependent regulation of social reward by oxytocin receptors in the ventral tegmental area. Neuropsychopharmacology, 44(4), 785–792. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-018-0262-y

Farage, M. A., Osborn, T. W., & MacLean, A. B. (2009). Cognitive, sensory, and emotional changes associated with the menstrual cycle: A review. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 280(4), 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-009-1192-1

Goldstein, J. M., Seidman, L. J., Horton, N. J., Makris, N., Kennedy, D. N., Caviness, V. S., Faraone, S. V., & Tsuang, M. T. (2001). Normal sexual dimorphism of the adult human brain assessed by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Cerebral Cortex, 11(6), 490–497. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/11.6.490

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: Behavior, physiology, and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(2), 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.2.221

Halpern, D. F., Benbow, C. P., Geary, D. C., Gur, R. C., Hyde, J. S., & Gernsbacher, M. A. (2007). The science of sex differences in science and mathematics. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 8(1), 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-1006.2007.00032.x

Hall, J. A., & Matsumoto, D. (2004). Gender differences in judgments of multiple emotions from facial expressions. Emotion, 4(2), 201–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.4.2.201

Herlitz, A., & Rehnman, J. (2008). Sex differences in episodic memory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(1), 52–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00547.x

Ingalhalikar, M., Smith, A., Parker, D., Satterthwaite, T. D., Elliott, M. A., Ruparel, K., Hakonarson, H., Gur, R. E., Gur, R. C., & Verma, R. (2014). Sex differences in the structural connectome of the human brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(2), 823–828. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1316909110

Joel, D., Berman, Z., Tavor, I., Wexler, N., Gaber, O., Stein, Y., Shefi, N., Pool, J., Urchs, S., Margulies, D. S., Liem, F., Hänggi, J., Jäncke, L., Assaf, Y., & others. (2015). Sex beyond the genitalia: The human brain mosaic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(50), 15468–15473. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1509654112

Kirkpatrick, L. A., & Davis, K. E. (1994). Attachment style, gender, and relationship stability: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(3), 502–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.3.502

Lenroot, R. K., & Giedd, J. N. (2010). Sex differences in the adolescent brain. Brain and Cognition, 72(1), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2009.10.008

Lisitsa, E. (2013, March 1). Weekend homework assignment: Physiological self-soothing. The Gottman Institute. https://www.gottman.com/blog/weekend-homework-assignment-physiological-self-soothing/

McRae, K., Ochsner, K. N., Mauss, I. B., Gabrieli, J. D. E., & Gross, J. J. (2008). Gender differences in emotion regulation: An fMRI study of cognitive reappraisal. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 11(2), 143–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430207088035

Newhoff, M., Treiman, D. M., Smith, K. A., & Steinmetz, P. N. (2015). Gender differences in human single neuron responses to male emotional faces. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, 499. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00499

Proverbio, A. M., Brignone, V., Matarazzo, S., Del Zotto, M., & Zani, A. (2008). Gender differences in hemispheric asymmetry for face processing. BMC Neuroscience, 9, 79. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-9-79

Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers: The acclaimed guide to stress, stress-related diseases, and coping (3rd ed.). Holt. https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780805073690/whyzebrasdontgetulcers

Schoep, M. E., Nieboer, T. E., van der Zanden, M., Braat, D. D. M., & Nap, A. W. (2019). The impact of menstrual symptoms on everyday life: A survey in the Netherlands and its impact on education and work. International Journal of Women’s Health, 11, 501–512. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S204616

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. https://www.guilford.com/books/The-Developing-Mind/Daniel-J-Siegel/9781462520671

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A. R., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411–429. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.107.3.411

Tunç, B., Solmaz, B., Parker, D., Satterthwaite, T. D., Elliott, M. A., Calkins, M. E., Ruparel, K., Gur, R. E., Gur, R. C., & Verma, R. (2016). Establishing a link between sex-related differences in the structural connectome and behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371(1688), 20150111. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0111 PubMed+1