The Bend Illusion: Why Older Women Overestimate Their Chances for Dating with Men

A Statistical and Psychological Analysis of Late-Life Relationship Dynamics

Introduction

Across affluent Western cities, many women in their 60s and 70s harbor a hopeful conviction: that somewhere beyond their city’s limits, perhaps in a mountain town like Bend, Redmand, Sisters or LaPine Oregon, there exists a charming, solvent, emotionally intelligent man who will see through age and find love.

This “Bend” fantasy is powerful, but largely detached from demographic and psychological reality.

This article examines the odds that a 65-year-old woman, who is not highly attractive, wanting a companion, or judgmental, can attract and keep a high-quality man over 65, someone healthy, fit, solvent, and emotionally mature. This paper draws on U.S. Census data, gerontological research, and statistical modeling to quantify the likelihood and unpack the deeper psychology of late-life attraction.

Demographic Reality: The Numbers Don’t Lie

By age 70, gender ratios in the dating pool heavily favor men.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2022), there are about 70 men for every 100 women over 65. Moreover:

~70 % of men in this age range are still married.

Only ~48 % of women are married, meaning single women outnumber single men nearly 5 to 2.

For every eligible single man over 70, there are two or more single women seeking him.

Even among the unmarried, men repartner more often than women.

In Repartnering After Gray Divorce (Carr et al., 2018), about 22 % of women formed new unions within 10 years versus 37 % of men.

A Bowling Green State University report (Westrick & Payne, 2021) shows remarriage rates plummet with age:

Women 70+ ≈ 0.1–0.3 % per year

Men 70+ ≈ 1–3 % per year

Thus, the odds are already small before personality, geography, or selectivity are factored in.

Behavioral Economics of Desire

Dating data reveal strong asymmetry: men’s desirability peaks in midlife, women’s declines continuously.

In the landmark study Aspirational Pursuit of Mates in Online Dating Markets (Science Advances, 2018), Bruch & Newman found:

Women’s perceived desirability peaks at 18–22 and declines thereafter.

Men’s desirability peaks near 50 and remains stable well into their 60s.

This dynamic persists offline.

A 72-year-old man who is fit, emotionally balanced, and affluent, especially in a lifestyle hub like Bend — can attract women in their 50s and 60s. Conversely, an average-looking 70-year-old woman faces intense competition and declining male interest.

Psychological Realities: Validation, Judgment, and Attraction

High-value older men avoid partners who project neediness, criticism, or emotional volatility. They prize serenity, autonomy, and appreciation, traits that preserve peace and companionship.

Research in Social and Emotional Aging (Carstensen et al., 2011) shows that men in later life regulate emotions by avoiding drama and prioritizing relationships that “add peace, not tension.”

Women who contact men with the energy of validation-seeking or judgment trigger avoidance rather than curiosity.

A 70-year-old woman writing to a Bend man she’s never met, particularly if her communication centers on an ambigous interest, faces emotional and statistical headwinds simultaneously.

Geographic Friction: The Portland-to-Bend Gap

Distance is a powerful deterrent. Surveys of older daters (AARP, 2024; SeniorList Research, 2025) indicate that:

Over 70 % of adults 65+ prefer partners within 50 miles.

Fewer than 15 % are open to relocating.

For example, Eugene, Ashland and Portland are separated from Bend in a three-hour drive, which creates logistical strain and cultural distance, urban-progressive versus outdoor-affluent ethos. A Bend man has ample local options and little incentive to nurture long-distance communication unless the woman’s presentation is compelling and emotionally congruent.

Quantifying the Odds: A Simple Statistical Model

Let us formalize the probability framework of women finding a partner in Bend Oregon if they live in cities that are more than 100 miles away.

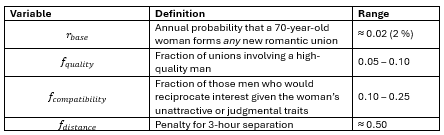

Parameters Estimates

The effective annual probability of securing such a partner:

Over 10 years:

P10=1−(1−reff)10≈0.0015=0.15%P_{10} = 1 - (1 - r_{eff})^{10} \approx 0.0015 = 0.15 \%P10=1−(1−reff)10≈0.0015=0.15%

That’s roughly 1 chance in 700 over a decade, an order of magnitude lower than the remarriage rate for average older women.

Even under optimistic assumptions, cumulative probabilities rarely exceed 0.5 % (1 in 200). Margins of error are dominated by modeling uncertainty; a realistic confidence band is 0.01 %–1 % over ten years.

Interpreting the Numbers

This modeling shows that demographic scarcity, geography, and interpersonal style compound multiplicatively. Even attractive, emotionally healthy older women face long odds in finding high-caliber partners; for those lacking self-awareness, the probability approaches zero.

Key Takeaways

Statistical scarcity: too few eligible men.

Behavioral mismatch: judgmental or needy styles repel emotionally healthy men.

Geographic friction: cross-regional courting halves response rates.

Cultural asymmetry: Bend men enjoy local abundance; Portland women imagine scarcity as destiny.

Men’s Apprehension About Marriage and Emotional Risk

Men’s divorce rates have shaped modern male caution.

The CDC Vital Statistics Report (2023) shows that remarried men over 60 face a ~25 % lifetime chance of another divorce, a costly risk. A 75% risk if they have divorced 2 or more times already.

Sociologists note a lingering apprehension among older men to “re-risk” intimacy, especially those with assets and adult children (Pew Research, 2014). Yet, paradoxically, men remarry more often than women. This duality reflects a shift: older men are selective and slow to commit but still open to companionship that enhances quality of life, not tension or conflict.

Men Alone vs. Women Alone

Men’s Contented Solitude

Research in Frontiers in Psychology (2022) and Journal of Gerontology (2019) finds that men often report stable life satisfaction when living alone, provided they maintain hobbies, social routines, and autonomy. Many men view solitude as peaceful rather than emotionally struggle or punitive.

Women’s Emotional Vulnerability

Older women, by contrast, show higher loneliness and depression indices when unpartnered (Carr & Freedman, 2018). They often experience relational absence as identity loss, not lifestyle freedom. This asymmetry fuels the “reach for connection” that underlies the Portland-to-Bend romantic fantasy.

Are Older Men Looking for Someone to Die With, or to Live With?

The evidence suggests that older men are not seeking caretakers or companions in decline, but partners to age with, not die with.

Qualitative studies in The Journal of Aging Studies (2021) describe men’s ideal late-life partner as “healthy, capable, attractive enough, and emotionally easy.” They seek to share vitality, not share decline.

This shift reframes late-life love: high-value men are future-focused even in their seventies. They are attracted to women who mirror that stance, curious, lively, self-contained, and capable of joy.

Conclusion: The Arithmetic of Illusion

The “Portland-to-Bend” fantasy encapsulates the emotional misalignment that traps many older women. The hard data, gender ratios, repartnering rates, distance penalties, and behavioral patterns converge on one conclusion:

The odds are not simply low; they are vanishingly small unless the woman herself evolves.

Statistically, fewer than 1 in 200 such women will form a lasting partnership with a high-value man across a regional divide. Psychologically, the path forward lies not in pursuit but in self-possession: building emotional independence, authenticity, and warmth. Because the truth is that high-value older men are not looking for someone to die with. They are looking for someone who still knows how to live.

References

Bruch, E. E., & Newman, M. E. J. (2018). Aspirational Pursuit of Mates in Online Dating Markets. Science Advances, American Association for the Advancement of Science. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aap9815

Carr, D., Freedman, V. A., Cornman, J., & Schwarz, N. (2018). Repartnering After Gray Divorce: Gender, Health, and Financial Well-Being. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, Oxford University Press. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6450723/

Carstensen, L. L., et al. (2011). Social and Emotional Aging. Annual Review of Psychology, Annual Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100448

National Center for Family & Marriage Research (2021). Remarriage Rate, 2021 (FP-23-19). Bowling Green State University. https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/westrick-payne-remarriage-rate-2021-fp-23-19.html

U.S. Census Bureau (2022). America’s Families and Living Arrangements. https://www.census.gov/topics/families.html

Pew Research Center (2014). The Demographics of Remarriage. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2014/11/14/chapter-2-the-demographics-of-remarriage/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2023). National Vital Statistics Reports, Series 21 No. 45. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_21/sr21_045.pdf

Frontiers in Psychology (2022). Is Dating Behavior in Digital Contexts Driven by Evolutionary Mechanisms? https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.678439/full

SeniorList Research (2025). Why Are Only 1 in 3 Older Singles Open to Dating? https://www.theseniorlist.com/research/older-singles-dating-study/

MarketWatch (2018). Women Online Daters Peak at 18; Men Peak at 50. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/women-online-daters-peak-at-age-18-men-peak-at-50-2018-08-17

References (academic & government)

Aspirational Pursuit of Mates in Online Dating Markets (2018). American Association for the Advancement of Science (Science Advances). https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aap9815

Structure of Online Dating Markets in U.S. Cities (2019). Sociological Science. https://sociologicalscience.com/articles-v6-9-219/

Structure of Online Dating Markets in U.S. Cities (Open Access) (2019). National Institutes of Health / PMC. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6666423/

Repartnering After Gray Divorce: Gender, Health, and Financial Well-Being (2018). Oxford University Press (Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6450723/

Social and Emotional Aging (2011). Annual Reviews (Annual Review of Psychology). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19575618/

America’s Families and Living Arrangements: 2022 (2022). U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2022/demo/families/cps-2022.html

Remarriage Rate, 2021 (FP-23-19) (2023). National Center for Family & Marriage Research, Bowling Green State University. https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/westrick-payne-remarriage-rate-2021-fp-23-19.html

Remarriage Rate, 2021 (FP-23-19) [PDF] (2023). National Center for Family & Marriage Research, Bowling Green State University. https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/westrick-payne-remarriage-rate-2021-fp-23-19.pdf

Chapter 2: The Demographics of Remarriage (2014). Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2014/11/14/chapter-2-the-demographics-of-remarriage/

Chapter 1: Trends in Remarriage in the U.S. (2014). Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2014/11/14/chapter-1-trends-in-remarriage-in-the-u-s/

Remarriages and Subsequent Divorces (1991). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (National Vital Statistics, Series 21, No. 45). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_21/sr21_045.pdf

References (magazines, newspapers & web media)

Women Online Daters Peak at 18; Men Peak at 50 (2018). MarketWatch. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/women-online-daters-peak-at-age-18-men-peak-at-50-2018-08-17

Men Want to Remarry; Women Are ‘Meh’ (2014). TIME Magazine. https://time.com/3584827/pew-marriage-divorce-remarriage/

One Husband Is Enough: Women in Their 60s See No Need to Remarry (2024). The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/lifestyle/relationships/boomer-women-divorce-remarried-84312184

Out of Your League? Study Shows Most Online Daters Seek More Desirable Mates (2018). Phys.org (Santa Fe Institute news release). https://phys.org/news/2018-08-league-online-daters-desirable.html

Online Romance Is Local, but Not All Locales Are the Same (2019). Santa Fe Institute. https://www.santafe.edu/news-center/news/study-online-romance-local-not-all-locales-are-same

Why Are Only 1 in 3 Older Singles Open to Dating? (2025). TheSeniorList. https://www.theseniorlist.com/research/older-singles-dating-study/