Modern Love Needs a Reset, and So Do the Apps

Mentor Research (2025)

The Red Pill or the Blue Pill Decision

"Take the blue pill and you stay in Tender. Take the red pill and you find connection in reality."

Contemporary online dating in Western societies can be more deeply understood through the theoretical lenses of Pierre Bourdieu and Charles Cooley, whose insights into symbolic interaction and social stratification shed light on the psychological and cultural undercurrents shaping dating behaviors.

Bourdieu’s concept of “symbolic capital” helps explain how users curate dating profiles to signal social desirability through coded indicators such as educational background, professional status, physical fitness, or aesthetic taste. These signals are forms of embodied and cultural capital designed to accrue social value within the dating marketplace. On apps like Tinder, Hinge, or Bumble, success often hinges not solely on attractiveness but on the alignment of “taste” with desirable social markers, travel photos, elite universities, witty captions, or high-status professions. Bourdieu’s framework highlights that dating platforms are not neutral spaces but digitized arenas of classed and gendered performance, where users leverage profile aesthetics to maximize attention from similarly positioned others.

Complementing this, Cooley’s concept of the “looking-glass self” describes how individuals form their sense of self through imagined perceptions of others. In online dating, this is amplified: swipes, likes, and matches provide real-time feedback loops that shape users’ self-perception, confidence, and emotional regulation. The dissonance between curated identities and real-life relational outcomes can lead to identity paradoxes, where individuals oscillate between portraying aspirational versions of themselves and yearning for authentic connection. In this environment, validation, both received and withheld, becomes a potent force in constructing digital self-worth.

Together, these frameworks offer a deeper understanding of why status signaling and identity curation are so central to Western online dating culture. They underscore that dating apps are not merely technological tools but social ecosystems embedded with hierarchies of taste, class, and relational capital. As such, they mirror broader dynamics of late-modern Western society, where the pursuit of intimacy is inseparable from the performance of identity and the negotiation of social value.

Bourdieu: Symbolic Capital and Digital Stratification

Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of symbolic capital, the prestige and value attributed to markers like education, income, physical appearance, and taste, plays a central role in online dating behavior. These platforms reward users who can successfully signal socially desirable traits. While these signals vary by app and subculture, they often replicate broader societal hierarchies.

On Hinge, a user might list:

“Harvard MBA | Management Consultant | Loves wine tastings and skiing in Zermatt”, blending cultural, economic, and educational capital into a profile designed to attract others who value elite status. Here, symbolic capital is both the currency and the filter.

Tinder, with its swipe-fast format, tends to amplify embodied capital, physical attractiveness. Profiles with gym photos, luxury travel, or high-fashion aesthetics often gain traction, reflecting a visual economy of desirability that privileges users with access to beauty, fitness, or wealth-enhancing experiences.

OkCupid, which allows for more text-based self-expression, adds a layer of cultural capital through sections like “favorite books, movies, music.” Users who mention NPR, Murakami, or Wes Anderson are often signaling intellectual or subcultural prestige. As Bourdieu argued, such “tastes” are not neutral, they align with class background and social mobility.

On Match, where users tend to seek long-term commitment, symbolic capital may manifest in subtle cues: job stability, home ownership, or family-oriented values. A user stating, “Financial planner, owns a home, loves Sunday BBQs with family,” is offering a form of relational capital, signaling readiness for traditional domestic life.

In all these platforms, taste becomes a mechanism of selection, reflecting Bourdieu’s claim that preferences are socially conditioned and stratified. Users with more socially recognized forms of capital are more likely to receive matches, reinforcing hierarchies even within ostensibly democratized digital spaces.

Cooley: The Looking-Glass Self and the Feedback Loop of Desire

Charles Cooley’s looking-glass self-concept explains how people form self-concepts based on how they think others perceive them. Online dating supercharges this process: users continuously absorb feedback in the form of likes, matches, and messages, adjusting their self-presentation accordingly.

On Tinder, users often experiment with profile photos and bios based on which versions generate more matches. A user who receives little engagement with a quirky or intellectual bio may swap it out for something more flirtatious or aspirational (e.g., “Adventurous traveler, always chasing sunsets”). If validation increases, the user may internalize that identity. Conversely, repeated rejection can erode confidence or foster resentment.

Hinge encourages emotional vulnerability and wit through prompts like “Dating me is like…” or “My most controversial opinion is…”. Users curate answers not necessarily to be authentic but to sound engaging. This leads to what Cooley would describe as a self-shaped by imagined evaluations, crafting responses based on what they think will be liked.

On OkCupid, where users answer extensive questionnaires, Cooley’s dynamic becomes even more pronounced. Users often report adjusting their answers to align with what they believe will attract high-status or like-minded partners. Someone who enjoys fast food might downplay it in favor of “farm-to-table” references, believing the latter is more appealing. The platform becomes a mirror, reflecting not just who someone is, but who they think they should be to gain acceptance.

Match users, who often seek long-term relationships, frequently experience identity paradoxes. A single father may portray himself as emotionally available and “ready to love again,” even if he harbors ambivalence, in order to meet perceived expectations. Users walk a tightrope between aspirational identity and perceived desirability.

The emotional consequences of this dynamic are significant. Users often equate match frequency with self-worth, or interpret ghosting as personal rejection. Cooley’s theory helps explain why online dating can feel simultaneously addictive and depleting, it is a constant performance for an imagined audience.

The Dark Side of Dating Apps

While dating apps promise connection, empowerment, and efficiency, they also carry significant psychological, social, and ethical risks. These include:

Gamification and Addiction

Apps like Tinder, Bumble, and Hinge use swipe-based mechanics that mimic slot machines. This creates dopamine loops, where users stay on the app not to form connections, but to seek validation through matches. This gamification can lead to compulsive usage and emotional burnout.

Objectification and Dehumanization

By design, dating apps reduce people to photos, taglines, and quick judgments. This encourages users to focus on surface-level traits (age, race, body type), which Bourdieu would interpret as filtering partners by visual capital rather than relational compatibility.

Self-Esteem and Rejection Sensitivity

Under Cooley’s looking-glass self, frequent ghosting, unmatching, and low engagement can lead users, especially men and marginalized individuals, to internalize rejection as a reflection of unworthiness, sometimes resulting in anxiety or resentment.

Harassment and Safety Risks

Women and LGBTQ+ users are disproportionately targeted for unwanted sexual messages, emotional manipulation, or stalking. Many platforms lack meaningful safeguards. These power asymmetries reflect deep structural inequalities that apps often fail to address.

Inequality and Market Imbalance

Data shows that dating apps are not meritocracies. A small percentage of men receive the majority of female attention, and women face constant filtering and harassment. This leads to frustration on both sides and a sense that the "market" is broken. Bourdieu would describe this as market stratification based on perceived social capital.

Bend Dating: A Sociological Alternative

Bend Dating is an emerging alternative dating model that seeks to counteract many of the pitfalls listed above. This model requires users to verify elements of their identity and intent, such as relationship goals, employment, values, or communication habits, often using human screeners, expert assessments, psychometric tools, biofeedback and polygraphs. The goal is to match users based on behavioral fit, shared life goals, psychological compatibility, and safety, not just surface traits that are subject to deception and the use of AI avatars.

Let’s analyze this using Bourdieu and Cooley’s frameworks:

Bourdieu: Symbolic Capital Redefined

Traditional apps reward visual and economic capital. Bend Dating inverts this hierarchy:

Instead of rewarding selfies or luxury travel, Bend Dating emphasizes relational capital, traits like empathy, self-regulation, reliability, character, life goals, and communication style.

Users may be matched based on shared values or long-term compatibility, rather than swiping on images.

Status is conferred not through traditional class markers, but through demonstrated social, psychological and emotional maturity.

In Bourdieu’s terms, Bend Dating redistributes symbolic capital by validating intimacy-related competencies over social privilege.

Example: A school teacher who volunteers weekly and wants children may rank higher in this ecosystem than a lawyer who posts flashy travel photos but wants no long-term relationship. This subverts typical capital hierarchies.

Cooley: Feedback Loop Toward Authenticity

Bend Dating minimizes performative self-presentation:

Because profiles are vetted or guided, users are less able to inflate or falsify who they are, especially so when presenting aspirational activities, and not the actual use of you time (e.g., I enjoy picnics, but I never have a picnic vs. I go on a picnic 2 times a month vs I enjoy going to food courts 6 times a month).

Feedback mechanisms (e.g., how well a match aligns with actual behavior) promote reflective self-awareness rather than compulsive self-editing.

Unlike Tinder or Bumble, where users might tweak profiles endlessly based on swipes, Bend Dating encourages a coherence between actual and presented self.

Example: A user who exaggerates their openness to kids or commitment may be flagged during structured interviews or value assessments, prompting reflection and honesty, not performance for the gaze of others.

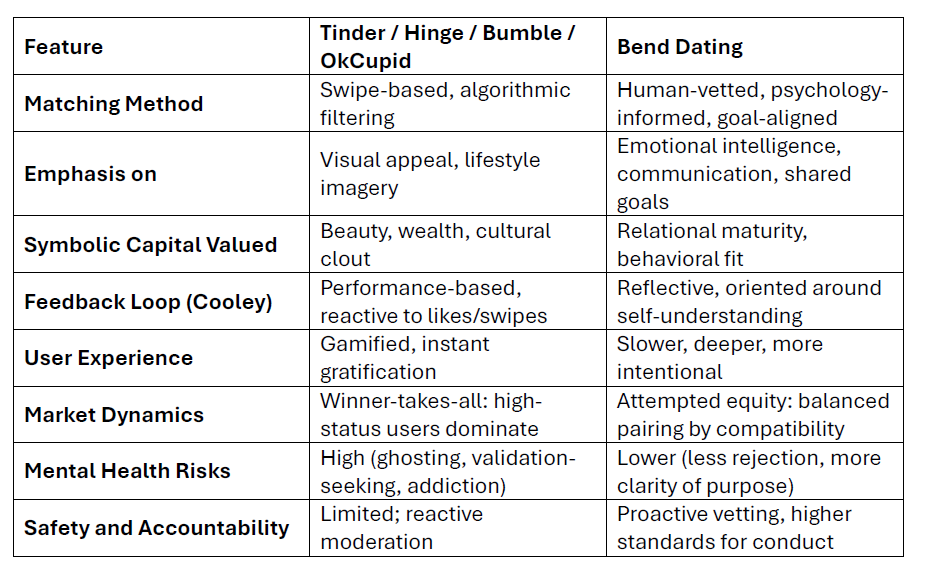

Bend Dating vs. Traditional Dating Apps

Summary and Integration Opportunity

Bend Dating offers a structurally different approach to digital intimacy, one that addresses the psychological and social deficiencies inherent in swipe-based systems. Through the lens of Bourdieu, it challenges the classed, visual, and performative logics of most apps by valuing emotional and relational capital. Through Cooley, it reorients dating toward self-awareness and congruence, not audience-pleasing.

Bend Dating serves as a case study of what a values-driven, accountability-centered dating model could look like. Its framework could also support a proposed intervention for improving male-female dating dynamics, particularly in contexts where high conflict and gender-based disappointment have eroded trust in digital spaces.

Related Articles

The Dating App Mirage

A sharp critique of swipe culture, this article argues that mainstream dating apps are engineered for engagement and profit rather than human connection, producing dependency, decision fatigue, ghosting, and distrust, then sketches the contours of a healthier, accountability-based alternative.

https://www.mentorresearch.org/the-dating-app-mirageSwipe Fatigue in America: The Unraveling of the Dating-App Dream

Charts U.S. disillusionment with apps amid layoffs at Match Group, Tinder’s user/revenue declines, and an FTC settlement, framing “swipe fatigue” as a cultural turn away from manipulative monetization and toward authenticity and offline connection.

https://www.mentorresearch.org/swipe-fatigue-in-america-the-unraveling-of-the-datingapp-dreamThe Policy Battles and Generation Divide of Swipe Culture

Explains how U.S. regulators are scrutinizing deceptive upsells and hard-to-cancel subscriptions while Gen Z rejects aloof, gamified courtship; it traces a split between habit-bound millennials and “yearners” favoring sincerity, and notes an emerging offline rebound.

https://www.mentorresearch.org/the-policy-battles-and-generational-divide-of-swipe-cultureCourts, Swipe Culture, and the Yearn for Something Real

Recounts the rise of Tinder’s swipe, industry retrenchment, and Hinge’s counter-positioning, then highlights regulation, cultural “yearning,” and a return to face-to-face courtship as Americans seek depth over engagement mechanics.

https://www.mentorresearch.org/courts-swipe-culture-and-the-yearn-for-something-realPower, Wealth, and Swipe Culture, The Economics of Attraction in U.S. Dating Apps

Analyzes the marketplace dynamics of desirability online, how money, status, and beauty concentrate attention; why men pay more for visibility; and how economic precarity fuels a “romance recession”, then calls for designs that elevate empathy and fairness.

https://www.mentorresearch.org/power-wealth-and-swipe-culture-the-economics-of-attraction-in-us-dating-appsThe Quiet Collapse of Courtship, Bonding, Marriage, Family, Community and Reproduction

Using Calhoun’s “Universe 25” as analogy, this long-form essay contends that abundance without purpose, amplified by digital performance culture, undermines roles, cooperation, and reproduction, arguing for renewed cultural scaffolding around commitment and family.

https://www.mentorresearch.org/the-quiet-collapse-of-courtship-bonding-marriage-family-community-and-reproductionMen are Disillusioned with Dating Apps in the US and England

Synthesizes surveys and narratives showing men’s low match rates, frequent ghosting, and burnout within skewed, pay-to-be-seen systems, linking these dynamics to declining self-esteem and a growing exodus from swipe-based dating.

https://www.mentorresearch.org/men-are-disillusioned-with-dating-apps-in-the-us-and-englandModern Love Needs a Reset, and So Do the Apps

Applies Bourdieu and Cooley to show how apps reward status signaling and mirror-driven self-presentation, then contrasts that with Bend Dating’s emphasis on relational capital and authenticity over performative profiles.

https://www.mentorresearch.org/modern-love-needs-a-reset-and-so-do-the-appsCriticisms of Tinder, Hinge, Match.com, Plenty of Fish, and OkCupid

A comparative review of major platforms’ recurring problems, addictive design, safety failures, data exploitation, algorithmic bias, and monetization conflicts—highlighting regulatory actions and investigative reporting.

https://www.mentorresearch.org/criticisms-of-tinder-hinge-matchcom-plenty-of-fish-and-okcupid